I mentioned last week that the last few cantos of Purgatorio are the most theological we’ve come across yet. We leave the realm of exciting plot that we were so used to in Inferno and a lot of Purgatorio and enter the lyrical mood that characterises Dante’s journey through heaven. As such, I invite everyone to read and enjoy the imagery we’re presented with, without too much influence from me.

I will, however, go through the rich symbolism of this canto, just to make it slightly easier for you to follow - Dante isn’t the most straightforward guy.

As usual, I like to think of this canto as happening in phases. The opening phase shows us a shift in Dante’s focus from Beatrice back to the procession. In the first moment of the canto we’re told that Beatrice has him completely transfixed, to the point where he can no longer perceive his surroundings through any senses other than sight. Beatrice is smiling and, transfixed by it, Dante has become all eyes in every sense but literal.

But, just like we can’t stare directly into the sun for more than a few moments, Dante can only look at that “holy smile” for so long before being left without sight. So he moves his gaze back onto the rest of the procession and notices that it has begun to turn on itself and change direction toward the east.

Just as silently and solemnly as they arrived, the procession moves across the deserted Garden of Eden (which Dante does not fail to remind us is entirely Eve’s fault) and eventually come what looks like a dead tree.

Here is where we enter the second phase of the canto. Through an embarrassingly thinly veiled allegory, Dante explores the theme of Adam and Eve’s fall from grace. The dead, leafless tree is none other than the Tree of Knowledge, from which the first humans chose to eat, thus severing their intimate relationship with and knowledge of God in favour of earthly knowledge. We know that this is the case from the procession’s choral accompaniment which conveniently narrates everything (see lines 43-46).

The Gryphon does the same thing. Stopping before the tree, Dante tells us that the “two-formed” creature (which you will remember from the previous couple of cantos is a representation of Christ), declares

‘In this way, all that’s true and just is saved’

Then, through an inexplicable motion considering the Gryphon has no hands that we know of, it takes the cross that connected it to Beatrice’s carriage and ties it to the tree. As if by magic, the tree comes back to life as if under the influence of an accelerated spring. The gist being that Christ’s sacrifice on the cross has the power to undo the original sin inherited from Adam and eve’s fall.

Phase three of the canto sees Dante suddenly fall asleep. This isn’t particularly surprising given the number of times we’ve seen him faint, sleep, dream, and - just earlier in this canto - lose his sight. Scholars interpret the narrative pause that Dante’s sleep enacts as symbol of his powerlessness/ speechlessness in the face of this new and holy landscape. In fact, he does not understand the hymn sung immediately after the tree’s revival and we can only assume how overwhelmed he is after seeing this symbolic reenactment of the Christ’s redemptive act.

When he wakes up from his sleep Dante realises that Beatrice is no longer with him. But before asking after her whereabouts, he describes the process of waking up at length and with vivid allusions to a couple of biblical episodes. The more straightforward one is that of Jesus raising Lazarus from the dead, which is echoed in line 72, where a mysterious voice tells Dante to “rise”.

The second, more complex one is laid out in the following verses, where Dante mentions the sleep that Peter, James and John were overcome by. This is in reference to an episode from the Gospel of Luke, chaper 9, where he tells of the Transfiguration of Christ. While in the mountains with Jesus, the three apostles falls asleep while Jesus prays/ communes with God. Upon awakening they find him completely changed, radiant and chatting to the Old Testament prophets Moses and Elias. Both his renewed physical appearance and his interaction with the prophets are a sign of Christ’s unique relation to God’s glory, which the apostles, given their fallible nature, are confused by.

Confusion is also the main feeling possessing Dante upon awakening - he wants his Beatrice. Seeing this, Matelda intervenes and point him towards the tree, where Beatrice is sitting on one of its giant roots.

Once again, Dante becomes entranced by her, this time by the sound of her speech, which invites him to pay attention to the chariot, now separated from the Gryphon.

At this point we’re given another piece of theological theatre which takes up the fourth and final phase of the canto in its entirety.

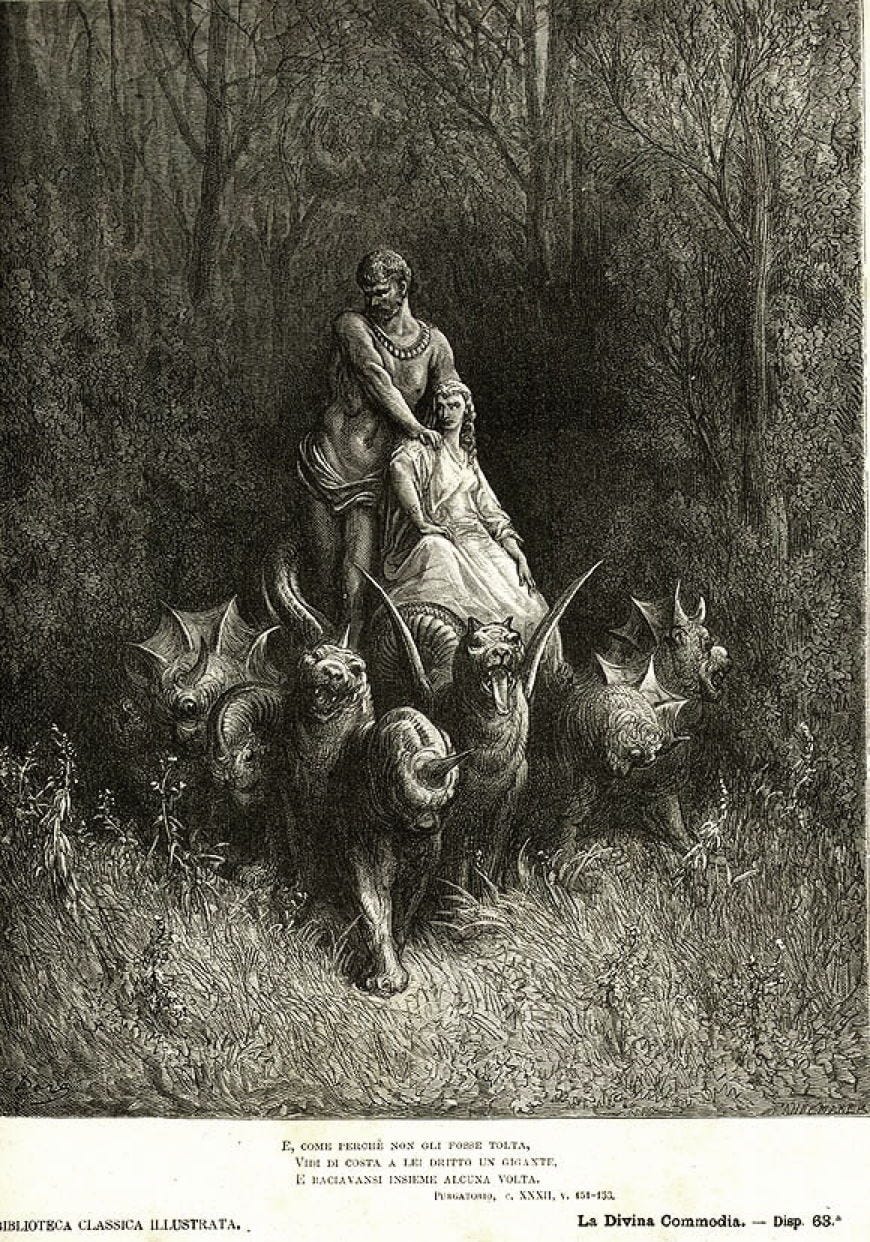

At a literal level, a bunch of odd events occur in rapid succession: and eagle appears and attacks the chariot. First it rips at the bark and flowers that decorate it. Then it conjures a vixen who comes and places herself comfortably in the carriage. Then, the eagle returns and “infects” the chariot with its touch, after which the vessel grows feathers. Immediately after that, a dragon crawls from the cracked earth and hurls its tail into the chariot, breaking it. The broken edges grow oxen heads and unicorn-like heads. Finally, among the monstrous heads, a whore appears, as well as her lover, a ferocious giant.

So what does this all mean?

The general consensus is that these 7 events represent the seven afflictions of the Church, from the early prosecutions at the hands of the Romans to the corruption contemporary to Dante.

The eagle’s first attack represents the persecutions christians suffered at the hands of Nero and Diocletian - the eagle being an emblem of the Roman Empire. The figure of the vixen represents false prophecy and refers to the early heresies that followed Christ’s ascension. The return of the eagle represents the moment in history when the Emperpr Constantine bestowed wealth and political power upon the Church, thus beginning the eternal battle between secular and spiritual power. The dragon is probably a representation of Islam and the threat Mohamed represented - in Dante’s view he was guilty of triggering a splintering of the Church, symbolised here by the smashing of the chariot into different pieces. The growing of multiple and different heads represents the further breakdown of the Church into smaller units based on the grands of land it received from multiple rulers through history - particularly Charlemagne and Pepin the younger (Dante was not a fan of the French influence on the Vatican).

The kings of France return incarnate in the figure of the giant, whom we see at the end of the canto locked in a kiss with a whore, a pretty obvious reference to the Whore of Babylon, representing the now completely corrupt Church, which Dante has been criticising throughout the whole poem.

Like I said, a lot of beautiful imagery containing even more narrative potential. I hope you’re enjoying these last few cantos as much as I am.

Next week is out last one!!

See you there x