Canto 30 takes the shape of four main phases. The first describes the way in which the procession described in the previous canto comes to a sudden halt. It opens with one of Dante’s classic bits of maritime imagery, in which we are told that the seven candelabra stop moving. The candelabra are likened to the seven stars of the constellation Ursa Minor, which used to be an important reference point for seafarers in Dante’s time. The allusion here is that in the way that seamen follow the seven stars, so should the good Christian follow the seven candelabra (which as we discussed last week, represent the 7 virtues).

So, “the people of the truth”, namely the prophets/apostles mentioned in the previous canto, have come to a stop. That being said, the scene is by no means static. Song continues to flow from them - one in particular sings the line “Veni, sponsa de Libano!” (Come with me from Lebanon, my spouse!) from the Song of Solomon, while others echo Alleluia and “Benedictus qui venis” (Blessed be the one who comes [to God]).

These are all biblical allusions to the reunion between Christ and his Church (often referred to as his “bride” as well). And, indeed, reunion is the main theme of this canto. On the one hand, Dante is about to enter the kingdom of God. On the other, in the second phase of the canto, he is about to come face to face with his beloved Beatrice.

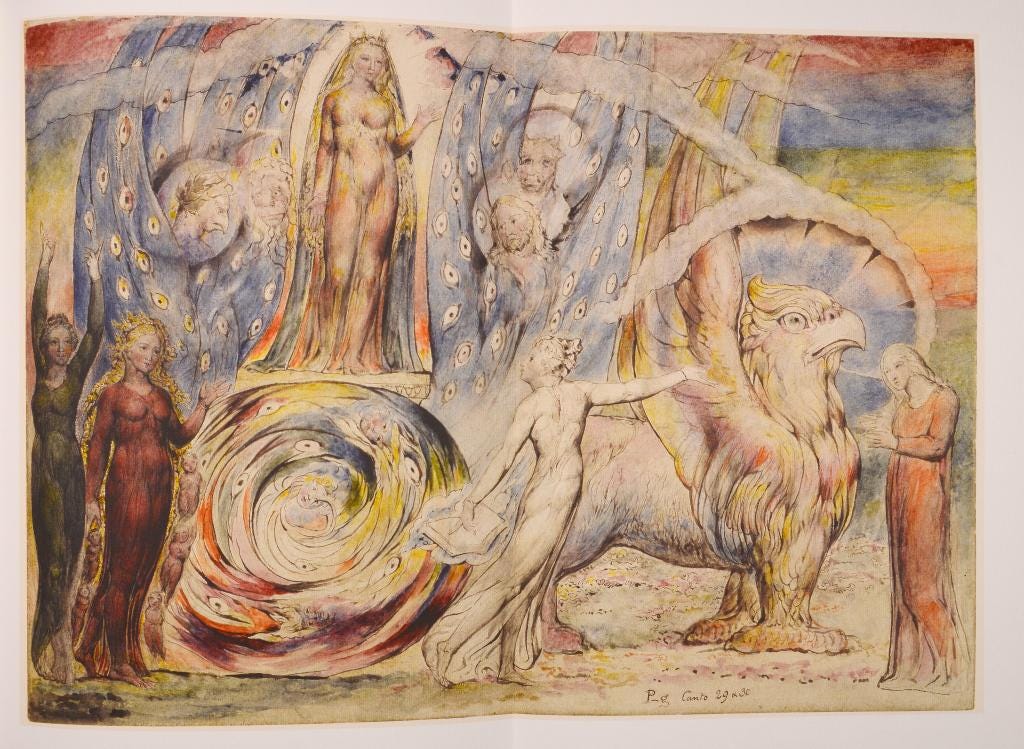

Her introduction is worthy of the anticipation created around her character all throughout the poem. She is described as appearing from beyond a drifting cloud of flowers held by a group of angels. She wears a green robe and a red dress and her face is hidden behind a thin white veil.

Coming off the heels of canto 29, it won’t be hard for us to identify these colour choices with the three theological virtues: faith, hope and charity.

Note here the description of her dress as “the colour of living flame” which is then juxtaposed to the “ancient flame” of line 48 - this is the woman whom Dante loved in life and the one who is about to initiate him to divine love.

But before he can feel the former, Dante is first reminded of the latter. Without even laying eyes directly onto her face, Dante confesses that an incontrollable trembling takes over his body, returning him to his boyhood, when he first saw Beatrice, aged nine.

Overwhelmed by the feeling he turns to Virgil and makes the confession out loud:

“There is not one gram

Of blood in me that does not tremble now.

I recognize the signs of ancient flame”

This last sentence is directly lifted from the Aeneid, where it is uttered by Dido, when in the underworld she remembers the love she had once felt for Aeneas. The choice can’t be anything other than a last tribute to Virgil, because just as he says the words and turns around, Virgil is gone forever. As if to return him to the present moment, Beatrice calls out to him by his given name. “Dante”, she says, “Virgil is gone, but don’t cry for this loss. There is something else you must weep for before”.

It is at this point that she finally confirms her identity. Form behind the veil, which we are told was fixed over her face with a crown of olive branches (again with the mixed Christian and pagan references), she tells Dante, as well as the rest of us “I am, truly, I am Beatrice”.

There are many things that Beatrice represents for Dante, both Dante the pilgrim and Dante the poet. She is a muse, she is the “donna gentile” which inspires love and through that love a higher form of art, she is a guide through Paradise and Dante’s saviour (as she explains in the last part of this canto). But here she appears as one of Dante’s harshest critics.

Some scholars have identified her here and in the following couple of cantos with a Christ figure. And in fact, she begins to question the pilgrim - “what right had you to venture to this mount? Did you not know that all are happy here?”

At this, Dante cannot whit stand even her veiled gaze, so he shifts his eyes to the river, in which he catches a glimpse of himself. And his reflection fills him with shame. This is a very different Dante to a couple of cantos ago when Virgil, in saying goodbye, encouraged him to trust his senses and his desire. Faced with Beatrice, who seems to reflects Dante - the real Dante - back at himself, the pilgrim realises that despite his spiritual journey he is still not fit for Paradise.

The realisation results in a sort of emotional breakdown, described in lines 85-99, where Dante compares his soul to the icy top of a mountain which suddenly thaws and floods the land below. Thus his ego, strengthened by Virgil’s kind words, crumbles and he begins to cry. In many ways you could say that at this particular moment Dante is caught between Virgil and Beatrice. Not just in their capacity as his guides but what they represent: Virgil is a stand in for reason and intellectual work, while Beatrice represents love. Now, before we fall too deep into Jordan Peterson-esque dichotomies I have to clarify that this is divine love, the kind of love that grants access to a greater kind of knowledge than any earthly philosophy. Which is different from the female=emotions; male=logic distinction characteristic of modern incel culture.

Now back to us.

In the last phase of the canto Beatrice expresses her judgment of Dante through a long speech in which she chastises him for his flailing loyalty after her death. She says that far too soon after her death, he renounced her memory in favour of another “mistress” and although he had been blessed by God to find the right path, he consciously chose the false way. The mistress in question is philosophy. What Dante is saying, through Beatrice’s character, is that once the object of his love disappeared, he took up a strictly intellectual existence. But earthly knowledge led his further and further away from God’s will, which how he ended up in the dark wood in which Inferno begins.

Now that he is reunited with the spirit of the woman whose earthly form inspired that first love in him, he can resume the journey on the right path.

But in order to do so, he must “pay a tax”. Although he has already symbolically done penance by climbing Mount Purgatory, Dante must confess his sin himself. Which he will do in the next canto. See you there!