We continue our journey through the 7th terrace, where the lustful are purging their sin by walking through a ring of fire extending around the mountain.

Immediately, we get to the matter of Dante’s corporality - as he tries to keep his distance from the fire by walking parallel to it, his body casts a shadow on the flames. I’ll pause here for a second to complain about my translation (the Robin Kirkpatrick), which says that Dante’s shadow “made fire seem fierier”. The Italian word, “rovente”, which can, of course, be translated as “fiery”, comes from the Latin verb rubeo, which means to “be red” or “become red”. In this context, I think what Dante is referring to is the way fire looks a deeper red in the dark than it does in the daytime (hence it is his shadow that makes the fire “rovente”) which is such a clever and subtle piece of imagery and it breaks my heart that while in Italian we get this pretty visual, the English reader of this edition gets “the fire seems fierier”. Like, really??

Rant over.

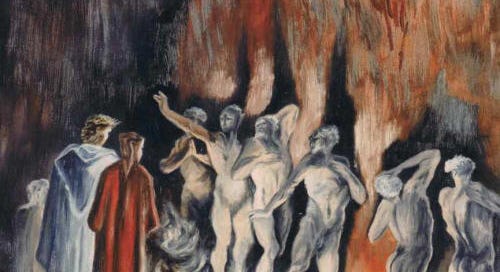

Just like every dead soul we’ve met throughout the entire poem, upon noticing that he casts a shadow, the lustful are curious to know Dante’s story. So they flock to him and start to ask questions. It’s worth noting the way the penitents move towards Dante but are careful not to get too close “where they should not be burned” (line 15). For several canto’s now we’ve seen that the penitents are different from the sinners of Inferno in that they rejoice at the opportunity to suffer. This is unsurprising since in hell the pain is as pointless as it is endless, whereas here pain =purgation and ultimately leads to salvation, albeit hundreds of years away.

This idea of a group of souls choosing to stay in the flames is reminiscent of the third ring of the 7th circle of hell, which held the violent against God. You will remember that the sinners were sentenced to an eternity of laying down (blasphemous), crouching (usurers), or running (sodomites) on a circle of burning sand while flakes of fire rained down on them. The sodomites were the only ones allowed to move so that they could get a bit of relief from the scorching heat.

I bring this up because, for reasons I haven’t really read much about (and the comment to my edition of Purgatorio seems to ignore completely), the terrace of Lust holds both people who have sinned of passion in heterosexual and homosexual relationships.

Dante says that before he can tell the penitents anything about himself, another group of spirits arrives through the flames behind them. The members of the two groups kiss and without stopping they shout offenses at each other, one group in reference to Sodom and Gomorrah and the other in reference to Pasiphae, before separating again.

We’ve already seen that each terrace comes with examples of the sin purged there and of the opposing virtue. As usual, the examples we get are both biblical and pagan in origin. The Sodom and Gomorrah cry is obviously related to the cities’ history of sexual depravity, particularly homosexuality. Pasiphae you will remember from the story of the Minotaur: she was the wife of Minos, who after seeing the Cretan Bull, asked Daedalus to build her wooden cow so she could climb in and have sex with it. The rest is… Well, not exactly history, but you get my point.

What is obvious here is that for some reason Dante chose to lump the gays and the straights together here, while in Inferno they were not only separated but homosexuality was punished several circles (and therefore degrees of gravity) deeper down than lust in heterosexual people. I wonder what made him decide that homosexuality, although still a sin, is less serious than it was when he wrote Inferno…

There are two things that I want to linger on from the central part of the canto. The first is that in explaining who he is and why he gets to walk through the realms of the afterlife while still alive, Dante says “I make this climb to be no longer blind” (line 58), which is my favourite thing he says about the purpose of his journey in the whole poem. It’s even better if you consider that he had struggled with his eyesight for most of his life.

The second is the way he chooses to tell us that homosexuality is being purged here. After telling the spirit addressing him about himself, Dante asks the still-nameless soul to name some of the lustful. The man says there are too many to name and also he doesn’t know all of them. But he confirms that the second crowd is full of people who ‘offended as did Caesar - who once heard “you queen!”’. This is in reference to a story by Suetonius according to which Julius Caesar had become a bottom for the king of Bithynia and his troops knew about it and even called him “queen”. Incredible gossip.

Anyway, in the last part of the canto, we find out that the man speaking is Guido Guinizzelli, an academic and jurist from Bologna, poet of the Stilnovo tradition and responsible for the concept that the capacity to love is the defining feature of true nobility and that love can only exists in noble hearts. Many scholars see Guinizzelli as Dante’s main influence in writing Vita Nova, the work he wrote to celebrate Beatrice after her death.

Dante is visibly flustered to be speaking to one of his main influences, but as we have already seen almost every time he meets a great poet, the person in question is actually super respectful and flattering to Dante… Probably nothing suspicious going on.

The same happens with the last person we meet in this canto, the Occitan poet Arnaut Daniel, known predominantly for his canzoni. Both Guinizzelli and Arnaut Daniel wrote in their mother tongues, so it’s not random that Dante praises both of them as some of the greatest poets - after all, he is writing in his vernacular, too.

The canto ends with a short speech from Arnaut himself, which Dante attempts to reproduce in the poet’s original language. I trust that whatever edition you’re reading provided a translation of this part as well. Ultimately, I don’t think the point of this last part is what Arnaut actually says, but rather, it’s an opportunity for Dante to show off his skill and knowledge of foreign vernaculars, as well as (in my opinion), an opportunity to show that vernacular languages in general are an appropriate medium for high literature.