This canto is all movement. Physically, lyrically, and narratively, there’s a non-stop back and forth to it that keeps us (and that includes Dante) on our toes.

From the opening, we are told that the walking and talking have not stopped. Dante and Forese are advancing along the 6th terrace catching up about whatever it is that 13th-century mates who haven’t seen each other since one of them died have to talk about.

This is until Dante asks for news of Forese’s sister, Piccarda, who we are told (with a Greek pagan reference to Mount Olympus) is enjoying herself in heaven. Then, seemingly unprompted, Forese offers to name a bunch of other people purging the sin of gluttony on the terrace, explaining that although they have been deprived of their likeness (remember they are skinny beyond recognition) they still have their names.

This is an interesting detail if you think back at the concept of personal identity all throughout Inferno: the way that every soul was desperate to be recognised and remembered or the way that the suicides were deprived of their bodies suggests that stripping a soul of its identity is yet another punitive layer of hell.

But here, among the saved, everyone still has their name attached to them, despite their (temporarily) corrupted appearance. Another big difference between these souls and those in hell is their attitude toward Dante. Last year we read of multiple instances in which the sinners were hostile to Dante in some way or other and, contrary to the recognition theme I mentioned above, some who even hated the fact that he knew them. But this is because in hell naming also meant shaming. Here the souls have no problem with being recognised.

Forese goes on to name a few historical figures - a pope here, a nobleman there - but the one person that captures Dante’s attention is Bonagiunta Orbicciani degli Overardi, a judge and notary from Lucca, who also dabbled in poetry around the same time as Dante.

In fact, the most hilarious bit of their interaction is that Bonagiunta recognises Dante as the author of Vita nuova, the part prose part verse work he wrote after Beatrice’s death. Not exactly the most humble introduction to a character.

But then, when Bonagiunta expresses admiration for Dante’s style, the latter explains that he was merely the scribe of that which Love told him to write. You have to give it to him, no one does false modesty like Dante. Especially when you consider that the false modesty is actually a dig at Bonagiunta and the poetry of his master, Guittone d’Arezzo, another famous poet of the time known for his particularly wordy and overly contrived style. By saying that he “simply follows” the dictates of Love, Dante claims a degree of spontaneity and a direct connection to the muses/poetic genius/ whatever you want to call it, than those who sit around and think about the hardest most complicated sentences they can possibly come up with.

Not only this, but he actually makes Bonagiunta acknowledge his poetic shortcomings. The fact that we haven’t really heard of Bonagiunta outside of this appearance in Dante’s own work makes it pretty clear that his work wasn’t very good. But did Dante have to add insult to injury?

Bonagiunta also adds a small prediction to the prophecy count - apparently, a woman has just been born (scholars have no idea who this might be) who will be very kind to Dante in the early years of his exile.

But we don’t have time to linger on Dante’s delicious pettiness or any more prophecies because immediately Forese jumps back into the conversation to say that he will have to leave Dante behind because he has been wasting precious time walking at his pace. But, like the great pal he is, he asks Dante when they’ll see each other again - which is basically asking Dante when he’s gonna die!

Dante says that he doesn’t know, but considering the state of Florence, fingers crossed it’s soon??? Hilarious exchange.

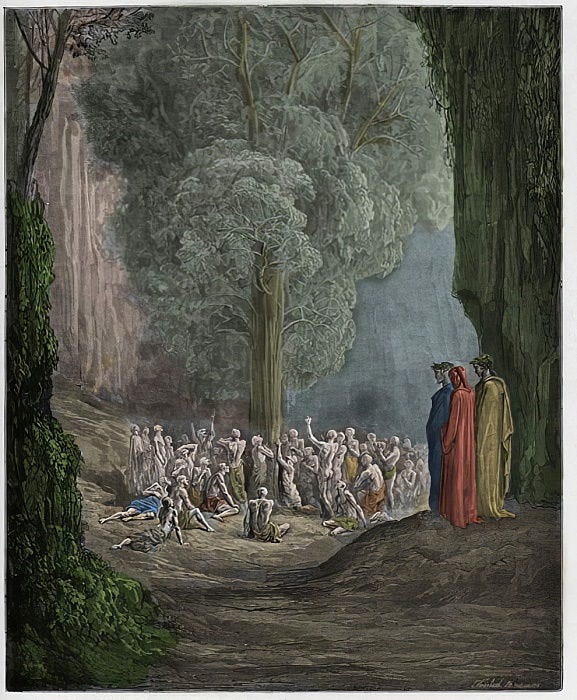

In the next section of the canto, the three poets come to a second tree, which just like the first is in the shape of an upside-down triangle. This one is also ripe with fruit and surrounded by spirits who cry and beg it for a bit of food until suddenly they lose interest in it. My reading here is that the humiliation drains the desire for earthly pleasure out of them, thus purging the sin they committed in life. It’s as if they lust below the tree until they have no lust left… Would be interested to hear other theories if you have any.

Like the previous tree, this one also has a voice between its branches, presenting the sinners with examples of gluttony punished. The first example is that of the centaurs who got drunk at a wedding and tried to rape the women guests but were killed by Theseus.

The second is from a biblical episode in which the Hebrew general Gideon forbids some of his soldiers who had indulged their appetites to partake in the battle against Midian and get a share of the spoils. As we’ve been accustomed to, these examples draw from Christian and pagan traditions.

The last phase of the canto brings us back to Dante and the poets, who have been walking in silence for 1000 steps, and suddenly they hear a disembodied voice ask where they’re off to so deep in thought. The voice belongs to the angel that guards the staircase to the 7th terrace.

We don’t get a description of it beyond being told that it has an oxymoronic presence: it’s more red and bright than the hottest furnace, but its physical proximity sends a cooling breeze toward Dante. Like all the other angels, it erases one of the Ps from Dante’s forehead - the penultimate one! - and shares a few words of praise and beatitude. But instead of transcribing a Pslam verse, Dante presents his own idea of what it means to be blessed: to feel a hungering continuously, but in a just and measured way. It’s unclear what this looks like in practical terms, but it seems to me similar to the Epicurean concept of balanced enjoyment of life’s pleasures and not the ascetic renunciation that has been popular with Christianity at various points.