Our last canto ended with a terrible earthquake that left Dante with a thousand questions he didn’t dare ask. But this doesn’t mean they’re gone - in fact, canto 21 opens with the same burning desire to know what on Mount Purgatory is going on.

In true Divine Comedy style, Dante expresses his curiosity through a biblical image, more specifically the episode of Jesus’s meeting with a Samaritan woman told in the gospel of John. He says that his thirst for knowing the source of the earthquake was as intense as the thirst for salvation that plagued the Samaritan woman when Jesus revealed himself to her as Christ the son of God.

This is a significant image because, in that story, Jesus tells the woman that anyone who follows him will be granted salvation, which was not the case according to the Old Testament, according to which the Messiah was meant to come and save the chosen race, namely Jewish people. By telling a Samaritan woman that she can be saved if she believes in him, Jesus opens the path to salvation to anyone who will convert.

Dante doesn’t use this as an opening image randomly. One of the predominant themes of canto 21 is conversion, personified by the appearance of Dante and Virgil’s new travel companion, the Roman poet Statius. But let me not get ahead of myself.

As Dante thinks over the itching questions he - for some reason - doesn’t have the courage to pose to Virgil, a voice calls out to them. For Virgil, who has been struggling to find his way through Purgatory this whole time, this is an opportunity to ask for directions and/or details about this place that he is so unfamiliar with. So he does exactly that.

But since this new soul is a poet himself, he can’t not notice the subtext to Virgil’s propitiatory address in lines 16-18, where he wishes the man that the “heavenly council that keeps me bound in eternal exile, may grant you a place withing that happy court.”

So Statius asks the obvious: is you’re one of those souls that God won’t let into the upper realms, then how did you get here?

At which Virgil politely directly him to the Ps on Dante’s forehead, which are sufficient proof that at least one of them is allowed to travel freely. In fact, he explains, the thread of Dante’s life, which Clotho casts, hasn’t even been cut yet. This is a pagan reference to the three Fates or Moirae, sisters who oversaw the lives of humans. Clotho measured the thread, Lachesis spun it into the various events of the person’s life and Athropos cut it at the moment of death.

Virgil also explains what we already know: he himself is bound to Hell in eternity, but has been called upon to guide Dante as far as possible on his way among the dead, given that “his eyes as yet don’t see as our eyes do”.

This explanation over, Statius launches into a lengthy explanation of his own. Mount Purgatory is an incredibly static environment, he says. There are no winds or rains or fires to disturb its peace. Every tremor that might shake it happens through divine will. The earthquake they all just witnessed was a ritual marking of a soul’s purgation coming to an end. As it happens, it’s Statius himself who, after over 500 years of penance, has finally been granted permission to start his journey up into Heaven.

It’s interesting that Dante has chosen this particular historical figure to use as an example of what happens to the souls of Purgatory when they have finished atoning and can enter the Kingdom of God. Mostly because a few of the biographical details he makes Statius state about himself are not true. For instance, Statius was not from Toulouse, as he says in line 89. And more importantly, there is no historical evidence that Statius had converted to Christianity. So to have him here as the picture of the saved pagan man of letters is a choice. Especially when placed side by side with Virgil, who doesn’t get this redemptive treatment.

The second part of the encounter between the three sheds a tiny bit more light on Dante’s choice. After introducing himself as the celebrated author of Thebaid and the unfinished Achilleid, Statius reveals that “the seed” that sprang his passion for poetry was Virgil’s Aeneid. So influential was Virgil’s work that he would happily live another year in the pain of Purgatory if that meant that he could have lived at the same time and place as Virgil on Earth. Virgil’s reaction to this is so pure and wholesome, I always smile when reading this passage. Of course, in Dante’s literary eyes, Virgil is countless times the poet that Statius is. But from Virgil’s position as an eternal sinner, to be so highly spoken of by someone who has just received the grace of God is an immense honour.

Dante also smiles at this coincidence, but mostly because it’s funny to hear one of the poets he admires gush about someone else, and to see his favourite poet and guide blush at the compliment. The whole scene almost gives Dante the upper hand. As if he is the wise and collected voice of reason while the other two are temporarily incapacitated by their very big feelings.

But the overarching theme of this scene (which will continue in canto 22) is poetry and the power of poetry - sacred or spiritual - to inspire and inform the search for truth. Ultimately, if Virgil’s poetry wasn’t there to work its magic, pagan as it was, maybe Statius would have never converted. And we already know that without Virgil there would be no Dante: no Dante the pilgrim because the beasts in canto one would have probably eaten him alive, and no Dante the poet, because he owes so much of his style to Virgil’s work.

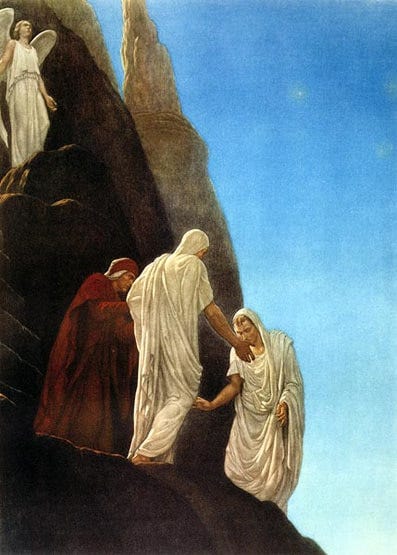

The canto closes with an even more endearing image of mutual admiration. Dante eventually tells Statius that actually, his guide is THE Virgil and the latter throws himself at his idol’s feet. Virgil reminds him that he cannot hug them because they are both nothing more than shades. In doing so, he affectionately calls him “brother”.

Statius in turn responds with the heart-melting

“Now you grasp how great

the love that warms my heart for you must be,

when I dismiss from mind our emptiness,

treating a shadow as a thing of weight.’