Canto 20 is a tricky one for most readers. Not because it’s actually difficult from a structural or conceptual perspective; it’s simply so dense with historical references that it becomes hard to follow for the modern reader. Luckily we’re going to get through it together.

The whole canto takes place on the 5th terrace, which as we saw last week, is where penitents are purging the sin of avarice. Canto 19 ended after Dante’s conversation with Pope Hadrian V and in this canto, he will speak to another historical figure, this time a politician. But before he gets to that, as usual, Dante likes to set the scene.

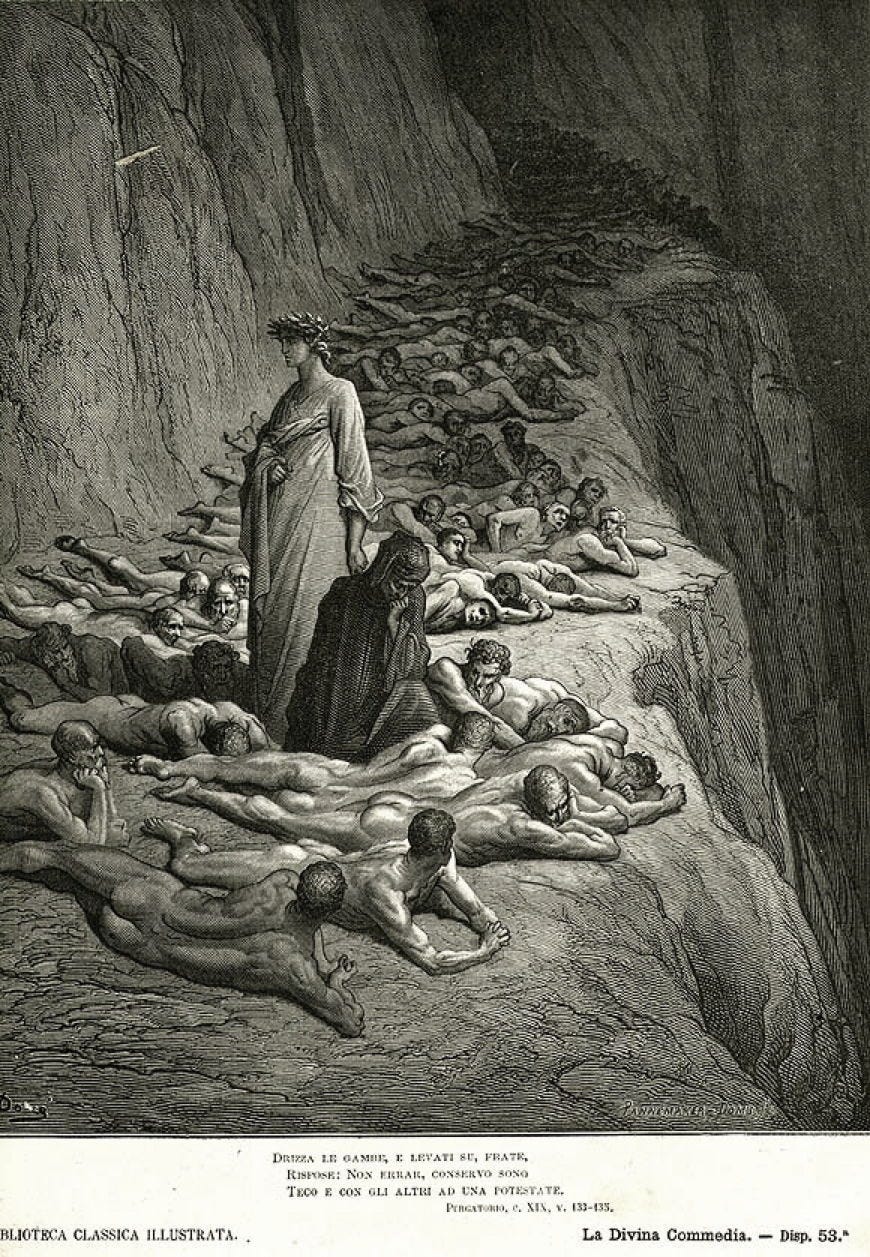

In the first lines of the canto Dante tells us that although his thirst for knowledge is not even close to being satisfied, he feels compelled to leave Hadrian behind and keep moving so as to not upset Virgil. So he starts walking again, but the ground on the 5th terrace is littered with so many penitents - who as you will remember from last week are lying face down on the ground and crying - that he can barely move.

He is both enraged and heartbroken at the sight of them, which triggers an impassioned speech against the “wolf bitch” whose corrupting influence has landed all these people here. You will remember from the very first canto of the Comedy that the wolf, more specifically the she-wolf, is one of the three beasts that blocks Dante’s path out of the dark wood and toward the sunny hill. We saw at the time that the dark wood symbolized sin, the sunny hill represented God and the three beasts each stood for a specific sin. The she-wolf was greed, which in Dante’s view was the worst of all the sins.

And here he is, restating that opinion in line 11, where he addresses the imaginary wolf saying “you snatch more prey than all the other beasts”.

The next verse also harks back at that first canto, where the she-wolf was described as painfully thin and growing hungrier the more she eats. Here we see her as “endlessly hollow” in her “hungering”.

And just like the first canto mentions a hound who will come and chase the she-wolf away (which at the time I wrote could be symbolic of Christ in the religious reading of the poem or an emperor in the secular reading). Here Dante seems to be referring exclusively to the second coming of Christ, whose arrival would finally rid humanity of avarice.

But despite the religious undertones, canto 20 remains a major political one. This becomes clear once Dante meets the central figure of the canto, whose identity is not revealed until the second half. First, we hear him.

As we’ve grown accustomed to for every level of Purgatory, as he makes his way through the 5th terrace, Dante is presented with examples of virtue - in this case voluntary poverty - as well as examples of avarice punished. A disembodied voice cries out words of worship first for the Virgin Mary, who gave birth in the humility of a stable, then for the Roman consul Fabricius, who refused an enormous bribe offered to him by the enemies of Rome to betray his troops and lastly for Saint Nicholas, who according to Christian tradition had saved three sisters from prostitution by gifting them golden coins every night when they slept to help them save up for their dowries.

Dante follows the sound of the voice and when he is finally close enough to the man, asks him about himself, promising that he will make sure to remember him once he makes it back to the world of the living.

But in a Divine Comedy first (at least this far), this soul doesn’t care for that. His name is Hugo Capet and, he says, he doesn’t expect anyone in Italy to pray for him. The reason for this, as it will emerge from the stories he has to tell, is that he was the founder of the Capetian dynasty, a family of French noblemen who replaced the Carolingian family as the main ruling family in Europe. As he explains in his rather lengthy speech, Hugo’s descendants were responsible for taking over the kingdom of Sicily and eventually forming an alliance (the terms of which they don’t actually mean to respect, it later turns out) with Pope Boniface VIII, through which they take over Florence and get Dante and a lot of his friends exiled.

Politically, the Capetian dynasty and their greed-based politics took Italy the closest it would be to becoming a nation-state for a while, which is why Dante places Hugo here. You might be thinking “actually Alina, that does not explain why Hugo is here and not in Hell”. And you would be right to think that. Not only is Hugo indirectly responsible for Dante’s exile, but the nation-state, which he and his sons were bringing about, is the exact opposite of the imperialist political model that Dante advocated for. Not to mention there is no historical evidence that Hugo ever repented for his views or asked for forgiveness.

However, instead of putting Hugo in hell, as Dante usually does with people he disapproves of, he brings him to Purgatory to use him as a spokesperson for Dante’s own political views. And is there a more powerful way to shove your own views down people’s throats than to make them come from the mouth of your opponents under the pretense that they have “come to their senses”?

We see in Hugo’s “prophecy” in line 70, not only a criticism of his family’s greed but a condemnation of his descendants as the new killers of Christ because of their work to block Italy’s return to a strong Holy Roman Empire. The language used in Hugo’s delivery of the prophecy, with the “O avarice” interjection in line 82 and the anaphora in lines 86 through 91, fuses the historical with the biblical. Not only are the enemies of the empire politically wrong (according to Dante’s political sympathies), but they are acting against the will of God. This is why greed, the main motor behind the actions of these men, is such a dangerous sin.

Hugo closes his diatribe with a list of examples of punished guilt, from Pygmalion who killed his uncle to take over his wealth, to Midas, who was killed by his own greed after he asked that everything he touched turn to gold - including his food!

He ends the list with an image of Crassus, one of the members of the Roman triumvirate alongside Caesar and Brutus, who was famous for his wealth and whose enemies filled his mouth with melted gold after he died.

Once again, Dante can tell that Virgil wants him to move on, and so he does, but suddenly an earthquake shakes Mount Purgatory. A thousand questions run through his mind, but too afraid to disturb his guide, Dante just continues walking.

Something tells me he won’t be silent for long, so I’ll meet you here next week to get some answers.