Canto 4 is the most intellectually ambitious one in the entire Purgatorio.

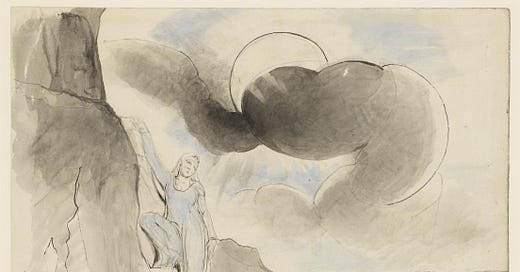

It opens with a description of how Dante continues his journey on the rocky mountain path, his body moving forward independently of his mind, which is still mulling over the conversation he had with Manfred in the previous canto.

He uses this image to give us a brief meditation on the nature of the soul.

At the time, the debate between Platonists and Aristotelians was in full swing, with Platonists believing humans had three souls, one for each type of human activity - vegetative, animal and rational - and Aristotelians saying that there was one soul with three separate functions.

Dante fell into the Aristotelian camp, and he uses the image of him walking and thinking at the same time as an argument in favour of Aristotle’s theory (Plato believed that the rational soul could dominate the other two, which can be interpreted as saying that when a person engages in deep thought all their other functions cease).

This image is also used to bring our attention to the passage of time - Dante is so absorbed by his thoughts that he barely notices the movement of the sun. And we know how important the movements of celestial bodies are to him!!

Intricate as his train of thought may be, however, the path of the mountain is even more complex. Dante begins to convey this idea through the image of the farmer who tries to stuff a small gap in his hedge, saying that the path that he and Virgil have to follow up the mountain is even smaller than this.

This “narrow path” biblical theme, is then followed by a geographical reference to the mountain fortress of San Leo, near the Italian city Urbino, and to the city of Noli, near the Ligurian sea, which was famous because it could only be reached via a staircase cut into the side of the mountain.

We get the point, the climb to heaven is arduous and often feels like it was designed exclusively for winged creatures. Should any humans want to make their way there, their desire will have to override any other sensation, from physical exhaustion to fear. Most of all, they have to keep believing that they will, eventually, get there.

Dante, as we’ve seen before, is not the best at believing. Luckily, Virgil is there to offer a word of encouragement. He tells Dante that they’re not too far from a “sheer slope” where they can rest a while and look back at the progress they’ve made so far, “for looking back will often cheer you up”.

As they rest, Dante asks for clarification as to why the sun is rising on the northern rather than the southern horizon. We know from the maps and notes included in the various appendices that come with almost every edition of the Comedy that this is because Mount Purgatory is situated in the southern hemisphere. However, Dante the pilgrim is only finding this out now.

Dante also asks how much farther they have to go, which always makes me think of the scene from Shrek where Donkey keeps asking “are we there yet?” until Shrek loses his shit.

Virgil, ever the patient man, explains that the climb up Mount Purgatory is always slower and more laborious in the beginning, but that it will only get easier as they move towards the top.

I love this image because it’s both super specific - in the sense that Dante pretty much made up the geography and metaphysics of Purgatory from scratch for the very narrow purpose that is this poem - and beautifully universal.

Think about all the times you’ve started a new venture, be it a new workout regime, a language class, or maybe you’ve tried to break a damaging habit. In all those things the start is always the hardest.

As beautiful as I might think Virgil’s words are, there’s always going t be someone who disagrees. As soon as Virgil finishes saying that the going will get easier, a voice somewhere behind them answers “hm, perhaps”.

Dante turns around and sees a bunch of people sitting under a rock “in postures, one might say, of negligence”. Among them, one seemed more worn out than the others, his head hanging between his knees, looking “more negligent than if his sister were Pure Indolence”. This moment of judgement is quickly followed by a moment of recognition though.

The speaker is Belacqua, a florentine acquaintance of Dante’s, known in the city for his indolence. And in fact, as soon as Dante recognises him he asks why he is sitting there: is he waiting for a guide or has he gone back to his old ways?

Belacqua’s answer clarifies that he had never changed his ways, to begin with. He says that since he - and we are given to understand this applies to the whole group he sits with - didn’t repent for his sins until the very last moment of his life, he now has to wait as many years as he lived without God before he is given the opportunity to begin his penitent journey up the mountain.

So we return to the theme of time, time passing excruciatingly slowly. We saw in canto 3 that the excommunicates walk towards God incredibly slowly. Now those who were slow in accepting God into their hearts are at a complete standstill. And as if to highlight this ethical nature of either wasting or making the most of one’s time, Virgil calls out to Dante and rushes him along further up the mountain.